Earlier this year, I took part in the Holocaust Education Institute held at the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust and the Museum of Tolerance. During each workshop, I was honored to hear the direct testimony of Holocaust survivors. As I listened to their stories, I heard an inspiring quotation from Elie Wiesel: “When you listen to a witness, you become a witness.” Because many of the direct witnesses of the Holocaust are aging, the realization that we could invite a survivor to Poly seemed urgent and important.

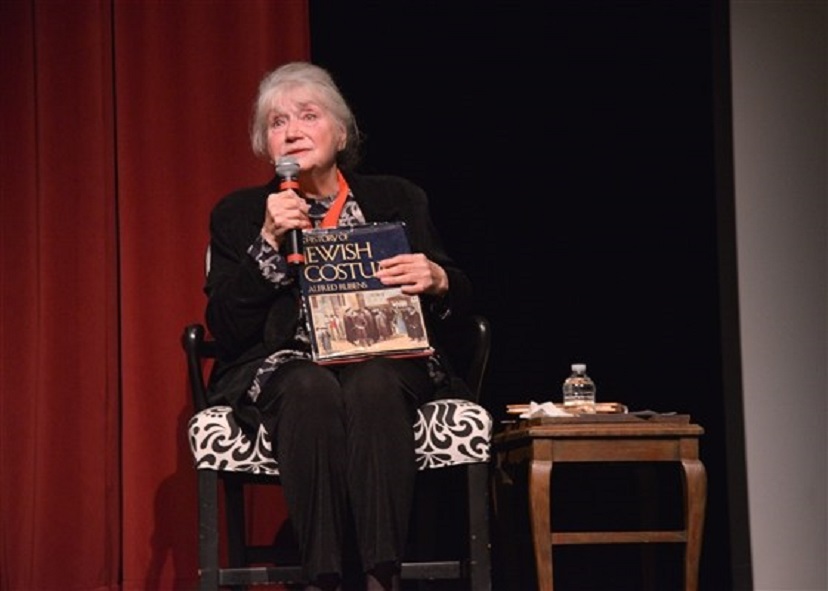

On Friday, Feb. 3, Trudie Strobel, a Holocaust survivor and artist of Judaic embroidery, came to share her compelling story of her survival during World War II at the hands of the Nazis. Jesse Miller, a Poly junior who has been awarded the Diller Teen Fellowship for Jewish leadership this year, introduced her:

Trudie is a great artist, a mother, a valued member of her synagogue, and a continued source of inspiration to me. The first time I saw Trudie’s work, it blew me away. Stitch by amazing stitch and bead by tiny bead, Trudie has sewn and woven many of the episodes of her life into tapestries, stunningly detailed works of art, each of which tells a story. And while many of Trudie’s stitched narratives illustrate atrocities that she has personally experienced and survived, all of her tapestries also communicate an element of hope and a call to perseverance.

Trudie Strobel is also a survivor of the Holocaust. And she has generously come here today to speak with us about that nearly unfathomable part of her life. Even before WWII, Trudie and her family endured years of extreme adversity at the hands of Stalin’s Cossacks. The Cossacks attacked and killed many Jewish men and women, and they pillaged Jewish farms and villages as part of the Soviet Pogrom. Trudie lost many close family members to this aimless violence. In addition to these attacks, when Trudie was only 4, she and her mother were taken by the Nazis and sent to a concentration camp.

She personally suffered the dark potentials of mankind and the horrific consequences of government policies of racism, xenophobia, and hate. But her trials didn’t end when the concentration camps were liberated in 1944. She was also the victim of U.S. non-interventionist policy that turned a blind eye on the refugees suffering an ocean away. After years of waiting to come to the United States, she did manage to gain entry into our country.

Trudie Strobel’s talk helped students more fully understand the dangers of totalitarianism and the costs of U.S. isolationism during WWII. Her talk inspired many questions from Poly students, including one from a visiting student from China who asked about Strobel’s decision to hide the personal trials she had endured from her own children until they were adults.

In discussing her own path, Strobel emphasized that art had lifted her out of a severe depression that had almost paralyzed her once her children had left home. In speaking to a psychiatrist about a memory of losing her doll, the only memento she had of her father, at the hands of a Nazi guard on the way to a labor camp, the doctor made a suggestion that she create a replica of the one she had lost. At this suggestion, Strobel began an artistic journey that would lead her to create many more dolls and works of art that she stitched by hand. She created dolls featuring the historic dress that many women had been forced to wear in different countries throughout the centuries as a stigma of Jewish identity. Some costumes had the Star of David; others wore yellow turbans or different colored shoes. While working on these costumes, Strobel began a transformative and healing process that allowed her to share her story with others and to bear witness to the traumatic experiences she had endured as a child. During Poly’s assembly, we were able to see a series of murals Strobel had sewn to visually represent some of her most powerful memories of the Holocaust in embroidered tapestries.

Our school community is deeply grateful for Trudie Strobel’s powerful words, her inspiring artwork, and the importance of remembrance as we guard against the dangers of totalitarianism. Above all, her message gave us inspiration of the power of art to heal us. Many students and faculty experienced the transformative power of Strobel’s direct testimony and were moved by her courage to bring us her wisdom, as we too became witnesses to the truth of the past.

Polytechnic School, 1030 E. California Blvd., Pasadena, (626) 396-6300 or visit www.polytechnic.org.